The Spellbook: On Education and Learning

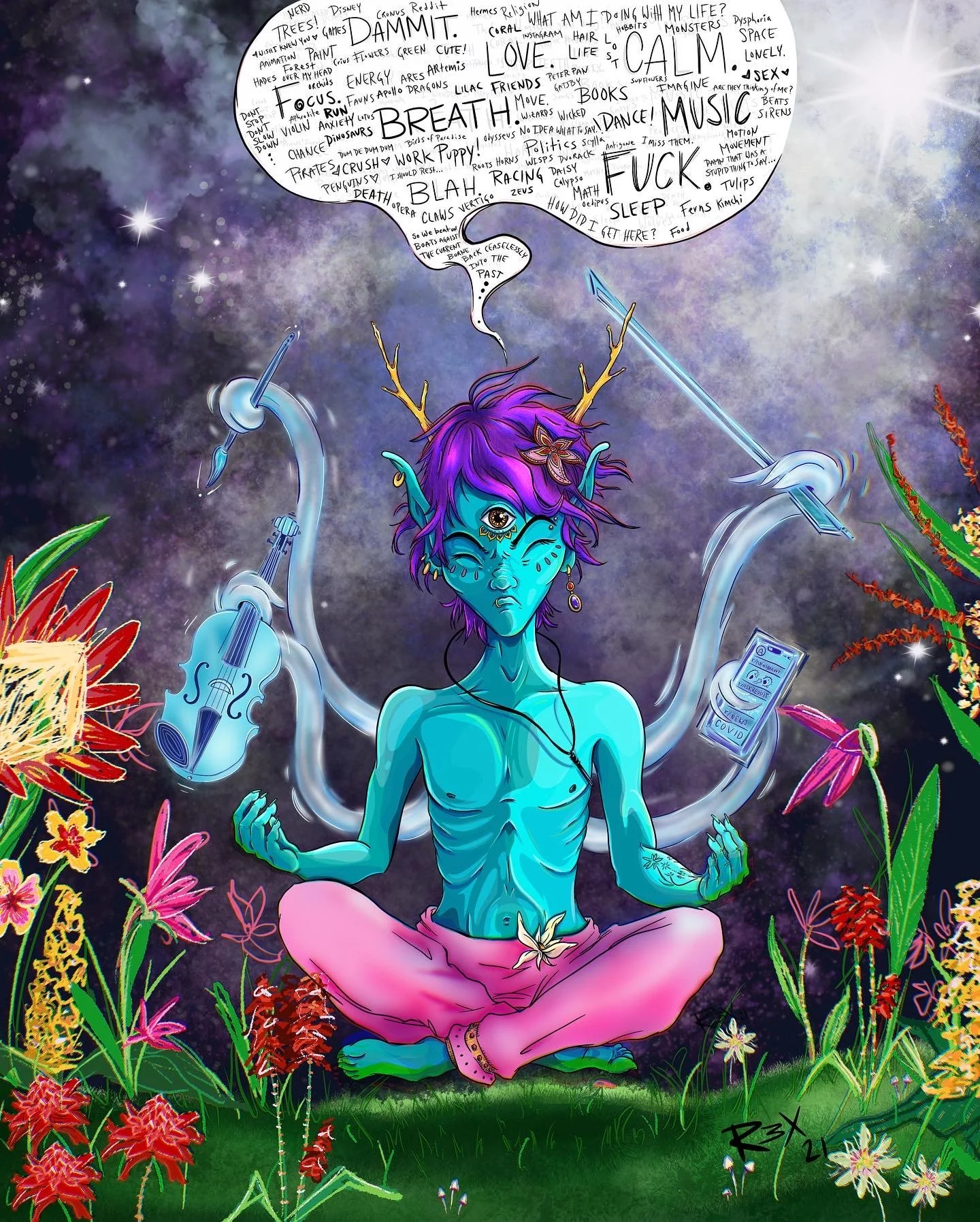

Ah the joys of meditation (me, 2021)

A few months ago, I was asked “if I’m going to be an artist, why should I have to take math classes? It’s ridiculous.” I spat out something along the lines of the most lame, practical answer that first crossed my mind, “so you can calculate a fair contract for your work and so people don’t take advantage of you.” I hate that answer. I’ve been thinking about it ever since.

I don’t hate it because it’s wrong. I hate it because it assumes a world view of scarcity and corruption. One that fails to appreciate the arts. I hate it most of all because it separates the world of art from its most natural source of inspiration—the natural world.

It would be like separating emotions from the world around you—you would no longer know why you feel the way you do and become lost in the waves.

Art without grounding drifts—swept out to sea—until it struggles from fatigue.

Likewise, to create without art is to deprive it, yourself, and others of soul.

It is the creation without thought Mary Shelley warns us about—

What happens in the aftermath of creation?

I’ve been thinking about education for the past several years now. The changes the pandemic brought along with the decade-and-half long, gradual shift to being unable to tinker and fix things yourself. The worry for future generations. But I think it all goes back to that first question, “why should I learn this?”

If I had a child, I think my answer would be, “because it opens magical worlds you can explore and play in.”

Learning is my greatest joy and I want others to experience that joy.

Learning gives us the language and the creative ability to zoom in and out to understand and manipulate the world around us.

I believe inside all of us is an artist. Inside every musician, engineer, merchant, explorer, wizard and warrior. Learning provides us the means of unlocking a soul’s resonance and only by learning to understanding the world around them, can you move in humble grace—dancing through worlds that awe and inspire you.

Learning is expansive. Learning is not just memorizing. Learning is the means of mapping systems and how they relate to each other.

We take our standard subjects—math, sciences, history, art, language, and physical education—stack them on top of each other to create a 3-dimensional map of connections. We can build out branches and assign classes of devotion in the pursuit of specified knowledge. But these subjects were never meant to be separate for long—because the natural world we live in, does not live in separation. To separate them is to deny truth.

Art

Learning reveals worlds and structures and systems that art has always evaluated and looked critically of. The first signs of art gave us insight into how neanderthals and the first homo sapiens perceived the world around them. From hand prints proclaiming self, to what they hunted and ate, to rituals around death and burial potential insights into first religions, and even the first dick pics and phallic objects. Throughout history it signifies cultural richness and gives means of asking provocative, open-ended questions. It gives the soul the voice and authority to speak on the very systems that inspire us to create—from socioeconomic systems to biology to architecture and psychology and so much more. Learning to evaluate collections of art of the same period tells us about economic gaps, power structures, societal values, their education, life style, and the health of the collective soul. It unites us. This is what makes art so powerful.

Music

Learning helps us understand music and why we feel it. What makes music work and why can we understand it? Learning about music integrates art with history, humanity, mathematics and sciences. Why do some note progressions work but others clash? How can we use a key change, even a single shift half-step down, to signal an emotional shift? How can we use maths and the circle of 5ths to better understand composition and harmony?

What does it take to hear a pitch, understand the key, and shift up or down to create resonance and harmony with another musician and then dancing within and outside that structure in improv or a jam with friends? When you’re learning about music, you’re not just learning about an instrument and how to pluck, strum, or bow. You are learning rhythm is an innate, practicable skill that can be written as a language as well as in numbers and then you realize—numbers are a language!

You can explore deeper. Dive down into which woods, fibers, and metals work best for resonance and tone. We can dive deeper into what is sound. We can learn about how sound is amplified and filtered not just through the use of pop filters on mics but through the use of digital signal processing to even cancel out noise. We can learn about how sound moves in wavelengths in order to create spaces that come alive when touched with the spirit of music. Suddenly, you find yourself wondering about the quietest rooms in the world and the architecture of amphitheaters.

So no, music is not just strumming. Learning gives us the appreciation for the continued art of exploring sound and resonance. It gives us understanding of compositions, emotional arcs, climaxes, akin to storytelling creating complex meaning without words while exploring the worlds of waves. How exhilarating!

Language

At its simplest level, language gives us means of communicating. But language is far more powerful than that. It is very difficult to imagine or give thought to something we do not have the language for. The pattern of a language can even shape societal structure and how an individual relates to others. Some languages are structured in relation to the self where as other languages force you to think about who is included with every conjugation. Some languages are built on binary sex modes and rigid gender roles, while others contain no pronouns and even exist within a society of a collective ‘we’. We can learn of our history from our language. “Bap meogeosseoyo/ have you eaten?” A Korean greeting born out of war time concern for our neighbors.

By learning other languages, we create pathways of how to think and express ourselves differently, not necessarily less or better, but differently. We learn stories carried from generation to generation—of rich history, recipes, tales that give their people fire. We see their care and their values. We can become curious and form loving, life-long relationships.

We can learn how to tell stories. Stories that create meaning. Stories that move the soul and, when read aloud, even have the ability to move the masses. We can choose to sow truths or deceit into the fields of our society for immediate gains and toss weeds into our neighbor’s yards so come winter, they bare shortages. Or we can choose to create and share stories that are diverse creating resilient, self-sustaining ecosystems, communities that attract beneficial pollinators while controlling pests, while improving our soil’s health. With language, we can create parables of comprehending the world around us to learn and implement healthy structures.

Language is one of the three core roots of magic. You can dream in images but if you cannot convey those dreams to those around you—if you cannot create and speak a spell—how can dreams be carried on the wind?

Engineering/Math and Sciences

Fundamentally, maths and sciences are just another language used to describe the world around us and, like language, we use it to manipulate and transform the world around us. We use numbers and place holders to assign values and manipulate them to solve for unknowns and create balance. We learn rules, how everything has a structure, even down to the shape of a leaf or the molecular structure of atoms and bonds. We can use those structures to inform our art—the study of how our eyes move across paintings and how we interact with design.

We can use precision for satisfying half-dovetailed furniture joints or to produce highly accurate, complex components for industries like aerospace, medical, defense, and automotive.

Delving far enough into maths and letters replace numbers—assigned value systems with an enticing puzzle beneath. Eventually, you realize this is a language—one you can map any problem, recognize patterns, and discover what is missing. You can learn of the systems like shrinkflation to discover how much more you’re paying per ounce and at what rate it’s increasing. You can use statistical analysis to map out quality assurance trends and how many resources are scrapped and where along the manufacturing pipeline it’s happening. You can even recognize every movement in animation is an arc and a bouncing ball problem and make adjustments based of the rate of change of movement.

We can do this and more. We’ve harnessed electricity and used it to build circuits—layering logic gates that translate voltage into binary, pulses of ones and zeros. With this language, we’ve created entire virtual landscapes, developed unique cryptographic keys to secure digital assets, and mapped genomes to help cure debilitating and life threatening diseases.

To some, these languages seem opaque and inaccessible—but for those who learn to read them, they offer the power to build bridges, design tools, and even save lives. In the age of silicon, we become wizards analyzing scrolls on magic mirrors.

But sometimes, from our towers we forget to zoom out or we’re zoomed out too far—eyes seeking the colonization of planets, mining resources, and other organisms. We forget the present and our humanity. We forget to how to communicate with others outside of these spaces. We forget the value of other disciplines. We forget to enjoy the dances in theaters as well as the dances of life. We forget to balance our most important equation—ourselves.

History

History is vital for understanding where we’ve been and where we’re going. Not just our political history but religious, art, science, and the pursuit of knowledge. Erase history—white-wash over it, delete files, burn books, art, medical research—and it sets humanity’s understanding and progress back decades.

Take for example the Institut fur Sexualwwissenschaft (Institute for Sexual Science) in Germany, the first sexology research center in the world. Its purpose was to create “scientific research on the entirety of sexual life” and to educate others on its findings. It pioneered research regarding gender and sexuality, including gay, transgender, and intersex topics. In addition, it offered other services including treatment for alcoholism, gynecological exams, marital and sex counseling, treatment for venereal diseases, and access to contraceptive treatments. Rather than attempting to cure homosexuality, it helped patients learn to navigate a homophobic society with the least discomfort as possible. It advocated for the right of intersex people born with ambiguous genitalia to choose their own sex upon reaching the age of 18 and assisted in sex reassignment surgeries. It contributed to early techniques for surgeries in facial feminizing and masculinization and helped curtail the arrest of crossdressers and transgender people advocating for people to wear clothes associated with opposite genders. In 1933, the institute and its libraries were burned and destroyed as a part of a Nazi government censorship program by youth brigades who burned its books and documents in the street.

The burning of the Institut fur Sexualwwissenschaft erased decades of groundbreaking work, particularly in understanding trans identities and medical transition. It sent a global chill through sex research: when the Nazi’s criminalized homosexuality and medicalized “deviance”, other countries to become cautious. Researchers feared political consequences and reputational damages—fears that lingered for decades. LGBTQ topics became taboo—seen as dangerous, immoral, or pathological rather than part of human diversity. In hindsight, modern scholars views the institute’s destruction as the loss of a golden age of understanding and compassion in queer and trans healthcare.

Today we see the echoes of this erasure—such as the removal of historical trans contributions to pivotal events such as the Stonewall Riots. In the U.S., Florida and other states have sought to censor educational materials that include Black history, queer authors, and the lived realities of trans people. Book bans target memoirs like Gender Queer by Maia Kebab and novels by authors of color. Entire curriculums rewritten to omit slavery or downplay colonization.

Globally, cultural genocides—from Palestine, to the burning of Mayan codices by Spanish clergy, to the destruction of indigenous languages—have aimed to erase knowledge that does not serve dominant power structures. When we lose access to these stories, we not only lose the past, but our ability to imagine different futures.

Learning is not just about information gathering and transfer. It’s memory, connection, and continuity. When we forget or erase history, especially those marginalized, we are breaking the chain of imagination, healing, and insight that future generations could build on—insight we can build on. To learn, we must protect what has already been learned—and remain open to uncomfortable truths. How can we learn to become great wizards, who learn even from little hobbits, if we do not care for our libraries?

Physical Education

Growing up, I didn’t prioritize physical education. Late into elementary school, I became too uncomfortable with my body and those around me. Now, I am healing, rewiring, and building habits from decades of neglect. Learning to be in your body, feel your body, and enjoy being in your body—life changing and boosts self-esteem. Physical education not only teaches you about your body and about sexual education (an option my parents chose to remove me from) but it has compounding cognitive, mental and emotional, social, and health benefits.

It improves focus and attention boosting blood flow to the brain enhancing concentration. It supports brain development in executive function, organizing, and impulse control. Physical activity is also linked to better memory retention and problem-solving. Physical education strengthens balance and gross motor skills.While I missed out on PE, the appreciation I now have for dance, yoga, and thru-hiking has allowed me to bridge wellness with other disciplines.

Learning how to move and breathe has helped me fall asleep faster and most importantly, stay asleep. Spending months in the woods has taught me life lessons on over-exertion and over-extension and to listen to my inner voice telling me to rest. It tested my teamwork and leadership skills navigating snakes, low water supplies, and sheer cliffs and crossings.

Physical education provides us with ideally safer spaces to learn rules, playing fair, and respecting others. Games teach us about each other’s abilities, how they’re suited for different roles, and different perspectives when we swap roles. Playing in gym or on the playgrounds or after school, gives us the space to run around and use our big imaginations. Being able to play pirates or ninjas was pivotal in learning about my desire to explore and learn about other worlds.

In learning about physical education, it teaches us how we can be graceful and beautiful in our own strength. It teaches us the joy of movement—adapting and growing. And for a spell to be properly cast, it requires your whole being—mind, body, and soul.

Government

How many of us actually pay attention while learning about our government? Of the People, for the People—and yet, propositions are written to confuse even the most learned. We all grow up learning about checks and balances and yet many of us don’t understand how the government works—at this point, neither does the U.S. government.

A government’s role is to serve its people by protecting freedoms, ensuring justice, and providing infrastructure for collective wellbeing. Learning about these systems and structures can inform us why something is happening, how it happens, and what we can do about it. Which is why weak governments strip away education first—to create a societal culture of anti-intellectualism in order to maintain control. A strong government values education to steer the next generation and country towards prosperity.

While most learn about the three branches—executive, Legislative, and Judicial—few understand how state and local laws can override guidelines and how much power lies in local school boards, city councils, and district attorneys. Many people become discouraged seeing an overwhelm of one color on their state map especially with voter suppression, gerrymandering, and other reasons why people don’t vote. But when citizens understand how redistricting affects their vote, or how bills are snuck through sessions, they’re more likely to speak up and vote with intention.

At a societal level, learning about the government with a mutual respect for the people lays a foundation of trust. It’s important to learn about media literacy so we can recognize mis-information from lies, recognize propaganda, and recognize when news is no longer news but entertainment. Learning about our government helps us hold it to a standard—one that encourages education and promotes health and safety. One that helps people understand why vaccines are important, how vaccines work, and a solid education helps conceptual understanding of exponential growth and herd immunity—concepts crucial during health crises and often misrepresented in media. Countries with strong civic education tend to have higher voter turnout, more trust in public institutions, and experience better health and equity.

A government is not some external force—it’s people, structures, and polices we collectively shape. The will of the people—there is no power like people power.

Sandbox

Learning is my greatest joy and I want others to experience that joy. I believe acquiring the joy of learning is one of the greatest gifts you can give yourself.

The more I learn, the more I realize how much I don’t know and that’s exciting!

If I become a parent one day, I want to instill in my child a sense of curiosity, of kindness and compassion, of not backing down from hard questions. I want my child to explore magical worlds and play. Learning how all these systems and structures come into play allows for a bigger sandbox—a sandbox we can all play in together. I want my child to have gigantic dreams—not a foolish dream of winning millions of dollars—but one of envisioning the world a better place than my parents and I have left it. Even if it means tearing down something I’ve created. That’s why education is so important. That’s why art, music, maths and sciences, history, government, all of it—is so important.

So next time, when someone asks, ‘why should I learn this?’—don’t just answer.

Invite them into the sandbox.

Open the spell book.

Show them what worlds await.